The ISPS Code and port obligations

The International Ship and Port Security Facility Code, or the ISPS Code, was adopted in December 2002. It’s designed to assist in the security of ships and port facilities through a set of defined measures, enabling them to “detect security threats and take preventative measures against security incidents affecting ships or port facilities used in international trade”.

This article will discuss port facilities' requirements under the ISPS Code to address security threats to vessels, crew and cargo. We will also provide some examples of how these procedures are implemented. We will cover the ISPS Code, the Port Facility Security Assessment (PFSA) and the Port Facility Security Plan (PFSP). Moreover, we will analyze the three prescribed security levels and how a port is required to maintain a security level while conducting operations. All while creating the least amount of disruption or delay to passengers, ship crew, visitors, goods and services.

The ISPS Code

The International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS code), was adopted in December 2002. The code went into effect in July 2004.

It established various definitions and procedures to unify the approach to physical security of ports and port facilities. It is accomplished initially through the Port Facility Security Assessment, or PFSA. It serves as the foundation for the following Port Facility Security Plan, or PFSP.

The PFSA is administered by the contracting government, a designated authority within that government, or a reputable security organisation. It is submitted to the contracting government for authorization.

Moreover, it should be evaluated frequently. We've visited ports in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia. We've seen some examples which can be considered best practice.

In Denmark, Risk Intelligence is one of four accredited RSOs and we regularly provide a range of services for clients based on the ISPS Code, such as the development of the Assessment (PFSA) on behalf of the Danish authorities, assistance with the preparation of the Plan (PFSP) with the port or terminal's Port Facility Security Officer (PFSO) and security team, and assistance with the drafting of a vessel's Ship Security Plan (SSP) with the Company Security Officer.

Security levels

Level 1: Normal - a port facility or vessel will normally operate;

Level 2: Heightened - the level applying for as long as there is a heightened risk of a security incident;

Level 3: Exceptional - the period of time when there is the probable or imminent risk of a security incident.

Normal operating status is Level 1. India takes a slightly different approach, with the majority of its ports operating at Level 2 for a substantial amount of time. Flag administrations have warned against Level 2 or Level 3 deployment for vessels in the Sea of Azov or near Ukrainian and Russian Black Sea ports.

PFSA considerations (Part B 15)

physical security

structural integrity

personnel protection systems

procedural policies

radio and telecommunications systems

relevant transportations infrastructure

utilities

all other areas that pose a risk

People involved in preparing the assessment should have prior experience in maritime, including with vessels and port operations. They should be knowledgeable with current security challenges and threats to both vessels and infrastructure. They should be familiar with how ports work and be informed of new security mitigation technology.

The assets and infrastructure relevant to the assessment should include:

accesses and approaches from both the land and the sea;

berthing areas and anchorages;

storage areas and cargo facilities;

roads, rail lines, and bridges within the facility;

power and water installations such as substations;

systems, which require external power, for example, radio, CCTV, communications, computer and other system networks;

the identification of potential threats;

the probability of threats’ occurrence in order to set a priority for security measures and services.

Therefore, interaction with outside agencies and local authorities is essential. The lesson to convey is that this evaluation should never be written in isolation.

PFSP considerations (Part B 16)

security organisation within the facility;

links to and with other relevant authorities to ensure continuous operation;

operational and physical security measures for Level 1;

additional measures to allow the port facility to assume and operate at Level 2 and 3 as required;

provide for regular audit and review of the Plan and to allow for amendments as changing situations may dictate;

detail the reporting procedures to the Contracting governments point of contact.

The port security organisation, led by the PFSO, must ensure that its personnel are properly trained and qualified, and that they are routinely exercised in their roles. A port security committee is comprised of members of local area response units, such as the police and emergency local councils. They should meet frequently, preferably at least twice a year.

Requirements for security level

Level 1 requirements include:

the minimum effective workforce required to operate;

the process for implementing modifications if the level increases.

If Level 2 is implemented:

to elevate and maintain safe operation, including the increase in personnel.

If Level 3 is accepted:

facilitating the access of emergency responders along with local and National Security Agency personnel, as well as their identification and accounting.

In addition:

the ability to suspend all or some poor operations and the power required to do so;

the ability to evacuate personnel from the facility to an unidentified safe area;

the procedure for the communication of pertinent information to vessels or at the anchorage must be determined.

the communication chain with the contracting government should be outlined in the plan.

Security Level 1| A port facility is to:

ensure the performance of all port facility duties;

control access to the port facility itself;

monitor the facility including anchoring and berthing areas;

monitor restricted areas ensuring only authorised personnel have access;

supervise the handling of cargo;

supervise the handling of ship’s stores;

ensure the availability of security communication.

Alternatively, a procedure for checking identification documents and a system for inspecting baggage should be implemented:

for personnel,

people in vehicles wishing to access the facility,

cargo that has been unloaded from or is ready to be embarked onto vessels.

Cargo that has been inspected and approved for loading or storage should be immediately identifiable. There should be a system in place to refuse entry and, if necessary, remove anyone without proper documentation. Establishment of designated locations for certain procedures, as well as restricted areas and children, to which only authorised staff have access.

Access control

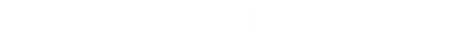

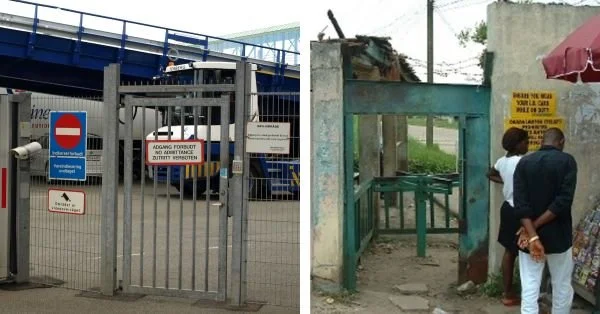

From the land side, the first thing a visitor sees is the main entrance. Port access control can be controlled or automated, with well-marked lanes and gates for pedestrians and vehicles.

There are port accesses where uniformed and alert personnel with distinct duties and an efficient external appearance are present. They act in a way that gives you a positive first impression. Meanwhile, there are also some port accesses that may not present that image and appear less organised and prepared.

Two different types of access control

We'll take a look at two quite different pedestrian access control methods that we discovered throughout our surveys.

Furthermore, we will cover corruption, which is widely recognised as a key security weakness not only within ports and port facilities, but at all levels of security. In our threat assessments, we use Transparency International Corruption Perception Index and and the Maritime Anti-Corruption Network based here in Copenhagen, recently released their Report summarising a decade of anonymous reporting of incidents by seafarers themselves, highlighting ports and areas where incidents have occurred and by whom (pilot, agent, authority etc).

On the right side, from the port in West Africa, this access point is a 24/7 entrance for pedestrians. The pay is fairly low, and the working conditions are similar. This situation, in which corruption is commonplace, makes it likely that this port will be accessed as needed by unauthorized persons.

The example on the left is from a port in Northern Europe. There are no staff at the gate, but that doesn't mean it isn't vulnerable to corruption. For example, the passcode may be shared with someone who should not have it. Then, by merely holding the gate open for them, cycled personnel could let many people in. Some gates, but not all, feature an alert function if the gate is left open for an extended period of time.

When there is a suspicion of a compromised system, ineffective administrators are unaware that these codes should be changed often. These automated systems appear to be cutting-edge and are frequently marketed as such. Access codes are useless if not changed when employees leave. The vessel must be aware of all personnel on the jetty and any personnel who desire to access the vessel.

Restricted areas should be clearly marked as such and, if necessary, have a separate entry. They should be staffed or secured with a list of key or pass card holders available to port or facility security. We encounter a couple of these deficiencies when we do surveys.

Commonly observed deficiencies

Despite being required by the ISPS code, training and exercise serials can be prioritised low due to expense and operational disruption. Security personnel may not know where to turn for help or what to do in a security situation.

All exercises should be done in three stages. The first step is a dry-run with the port's operating company, the PFSO, local authorities, and other workers. The situation is described, and the port responses are outlined in this tabletop exercise.

This exercise should be used to identify where manpower and other assets would be positioned during normal daily operations. This also outlines what communications will be commonly used, allowing the possibility of testing those communication routes prior to the exercise. Once the table topping is finished, the exercise can be performed, which is the second stage.

The third stage is the post exercise analysis, de-brief or wash-up. What worked well and what did not? Where should we concentrate our efforts? How have we collaborated with local authorities, vessels at berth, vessels at anchor or drifting offshore, with companies routinely operating within the port?

A walkthrough for possible responders to an emergency is one of the more routine exercises that a port might consider organising. This could be provided by the person in charge of that region. This enables people who will actually respond to analyse demands and requirements. Requests such as field of view, choke points and safe assembly areas.

We already discussed technology advances and cutting-edge security measures. However, they are of little use if they are not activated or if they are in the wrong spot. If they are not adequately maintained or if not enough trained staff are available to operate them. Under some cases, CCTV cameras have been moved alongside the window. This indicates that additional forces reposition them to point away from their initial aim. In certain occasions, some have not been subjected to a cleaning procedure on a regular basis.

The water side of a port appears to have the lowest level of security. We occasionally observe the security vessels that many ports claim to have patrolling their waterways.

This, however, varies based on the port and area. The image features examples from Southern Africa, the Middle East, East Africa, and the UK. We spend at least a full day and night at the sites we visit in order to watch these patrols personally.

Vessels should always rely on their own surveillance and mitigation capabilities against any potential threat. Using functionally tested communications and the ability to floodlight from the side, it is possible to light the area. The goal is to present your vessel as prepared and alert. In the majority of circumstances, potential perpetrators will go elsewhere for a more suitable target.

Challenges for the ISPS Code

More responsibility is placed on seafarers, and security-related activities are included into the role. That was put into the STCW regulations as the PTSD qualification. When the security level rises, port activities may experience delays or possibly be completely halted. This can result in higher costs and decreased efficiency.

Cybersecurity

The Russia-Ukraine conflict, which has suspended freight operations in almost all Ukrainian ports and raised security levels in geographic areas. There are evolving threats to ships that may differ from when the code was first implemented. In 2019, there have been attacks on vessels in the Gulf of Oman, as well as approaches from state back taxes.

Some of these attacks take place in port areas. They are within the responsibility of the port, which is where and how drones enter the threat picture. Cyber-related incidents are becoming a growing concern to vessels, ports, and companies.

Indeed, BIMCO is working on the fourth version of their cybersecurity guidelines for ships in collaboration with other organisations. Copenhagen Business School conducted a 2020 study on cybersecurity governance in Danish shipping. The International Association of Ports and Harbors developed cyber recommendations for ports and port facilities near the end of 2021. The question is whether the ASM code or the ISPS should incorporate cyber and whether "cyber risk management" term is better than "cybersecurity."

FAQ:

-

I think certainly it's a useful tool, but it should only be viewed as that. And yes, standards do vary, but it's claimed to be ISPS compliance. I see various standards of implementation when we do visits.

-

It increases the workload for vessels with already overburdened crews. However, companies will continue to attempt to schedule voyages to ports in areas where it is not recommended to travel.

-

The vessel can never 100% rely on the port to prevent unauthorised access to its surroundings. The one takeaway that anybody responsible for a vessel should take is that the ultimate responsibility lies with yourselves, with the lockout routine, with managing people who have access on board, property card routine, a proper gangway century.

The bottom line is that stevedores are often involved in stowaways incidents theft from the ship. So, they of course, depending on what type of ship you are, you will have different types and numbers of CEOs on the ship. But that poses a risk because the port doesn't know exactly what people are getting on board.

You have to be in a position where you're confident that you can positively identify every person that's on your vessel. And if you have a stevedore gang, you've got no way whatsoever of positively identifying who's on your vessel. And that should be the question that you ask yourself, for the duration of your port call, at any given moment of the day: can I positively identify everyone that's on here.

It doesn't benefit anybody financially to fix those security lapses. So, they're not being done.

-

We do have a Masters Observation Form, which we get back here at Risk Intelligence, but I think you'll find that because of the routine of life on board the ship, once the port call is finished, and you've disembarked the pilot, and you're away, your whole focus then goes on to the next port call. There really isn't the time because, okay, we got through that port call, it was good. We didn't have any major security issues, we might have had to give a stevedore company, a few dollars here. But that port call has been done, it's ticked off. And now we're looking forward to the next one.

Of course, as such, there's a procedure in place in a lot of the more reputable ports, to give feedback, and to make suggestions based on security related incidents that may or may not have affected your vessel. But for a stretched crew, that port call is done. It becomes normal course of business, normal routine of events.

Featured service products:

Contingency and continuity - Risk Intelligence provides a step-by-step process to optimised contingency management that helps clients establish a corporate business contingency programme.

ISPS services and training - our ISPS services and training programmes are designed to enable maritime operators to optimise their security planning and comply with international regulations and security standards.

Ship Security Plans (SSP) - developed by our advisory consultants in close cooperation with the Company Security Officer, the CSO. The plan is tailored to both fleet size and budget and can be provided as either a specific vessel document or as a template for vessel type(s), which can then be tailored by the CSO.